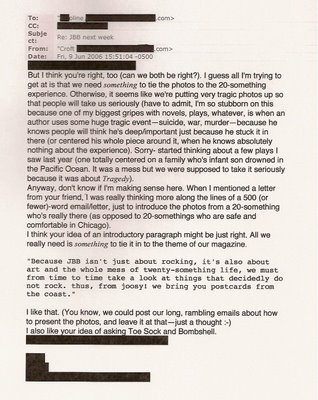

The Dananator's

The Dananator's

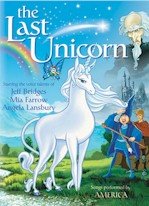

Read Everything ApproachIt didn’t take me long to discover that, as a writer, Dan Brown lacks a certain grace. After all, this gem was located on page two of

The Da Vinci Code: “‘You are lying.’ The man stared at him, perfectly immobile except for the glint in his ghostly eyes. ‘You and your brethren possess something that is not yours.’” Yet despite that last sentence and hundreds of others like it, Dan Brown possesses worldwide literary fame and a lot of money from selling 40 million copies of his novel. Unlike so many of his brethren, Brown has achieved what many an amateur novelist longs to do: publish a bestseller.

It’s common knowledge that bestsellers are not always the best books, and with greater fame and bigger book sales comes more intense scrutiny and criticism.

The Da Vinci Code is certainly no exception. Although the book claims the somewhat dubious accolades of

People,

The Denver Post, Clive Cussler, and Nelson DeMille on its jacket, it has been widely panned by the critics for its sloppy writing, predictable plotline, dubious history, and academic affectations.

So why am I reading it? When I walked into Barnes and Noble last week and became Dan Brown’s forty-million-and-first customer, I set into motion a bold new plan for my personal reading habits. This new plan is entitled Read Everything. I used to try to have standards, choosing what I planned to read with great care, electing to read only things that would further my knowledge of literature and my facility with language. I would look askance at the woman standing next to me on the CTA, clinging to a pole with one hand and a copy of the latest Nicholas Sparks novel in the other. I, in contrast, was prepared to dive into the copy of Thomas Hardy’s Jude the Obscure that rested snugly in my backpack. Where it had been stowed away for the last three weeks.

Truthfully, I just wasn’t into it. I should have been, because Thomas Hardy— a canonical English novelist—wrote it, and after all, I did just get my Masters in Humanities with a concentration in literature, and after all, I was teaching literature to college students, so certainly it would behoove me to bury myself in Hardy’s literary stylings for personal and professional gain. However, with copies of the Red Eye being free these days, how could Jude the Obscure possibly compete?

It couldn’t. I found that the weighty, intellectually stimulating books I had elected to read were not, in fact, read but instead hauled around like dead weight. Something had to be done, and with all the discussion of The Da Vinci Code, I saw a chance to break free from my own restrictions and read a book that had “Coming Soon to the Big Screen!” printed in gold over a sunburst on its cover.

The seed of the Read Everything plan was planted when I began my new job in the publishing industry. Seeing books in various stages of readiness is like seeing relatives in various stages of undress—unsettling at best, traumatizing at worst.

When I was younger I used to have the utmost respect for books as physical objects. I used to put off the moment when I had to crease the binding of a new volume, sometimes reading at an awkward angle for chapters and chapters. I would never dog-ear the pages to remember where I had stopped reading. Of course, these prohibitions relaxed slightly as I got further in school and needed to underline and highlight texts, but I think my primordial respect for books was closely tied to their physical format at some deep subconscious level. These pages, I would think, hold Ideas and Concepts and Great Narratives worthy of being put into Print, a feat which only Real Writers achieved.

Now that many of my waking hours revolve around proofreading, page passes, InDesign snafus, and margin tweaking, I feel a bit like a medical student in anatomy lab. It must be tempting for future doctors, having grown used to the sight of cadavers opened up on tables, to see everyone as so much tissue and gristle. There they are, my beloved books, lying on sterile tables slit from belly to chin—all their typos and flaws exposed, the arbitrary nature of their composition evident to all.

Seeing books that way, on a devastatingly leveled playing field, did not so much topple my admiration for the great as it elevated my opinion of the mundane. It cannot be denied that there are both good and bad books. What I am no longer certain of is whether it is incumbent upon us to give a damn about which is which as we select what to read. I have decided to do away with my own vetting process in favor of a glorious free for all.

We need bad books. While the great books, the golden tomes that manage to articulate the human experience with shimming cascades of beautiful language, should be lauded, bad books should be equally revered because good readers, and good writers, would be lost without them. And so no longer will I sort my books according to their perceived “worth” or judged by their author’s skill. Rather, the crap books I own will stand proudly alongside the ones of far greater literary merit. They have earned their place there by being both entertaining and didactic.

Bad books are fun to read. Although the The Da Vinci Code has elicited a flinch or an eye-roll from me once every three or four pages, those pages keep turning—and they’re not turning themselves. A massive conspiracy handed down throughout the ages by a secret society, the inherent corruption of one of the world’s largest and most influential religions, a high-octane anxiety-filled international chase, an undercurrent of sexual tension—sure, I’ll read it. Beats looking out the window at the Dan Ryan on my commuter train at 7:30 every morning.

Popular books are popular because they entertain. The Da Vinci Code may not be airtight in its scholarship or flawless in its turn of phrase, but the story is cool. Raise your hand if you saw the first or third film in the Indiana Jones series (we’ll put the second aside for a moment for the purity of the argument). Keep them up if you thought your viewing of them was a waste of three hours of your life. That’s what I thought. The Da Vinci Code is Indiana Jones in modern-day Europe, except the female gets a more substantial role. I have my complaints, but generally, I dig it. Of course, I’m not going to send an application into the Priory of Scion, but it was a fun read and an interesting take on the Catholic Church.

Truly bad writing can even be raised to an art form. We honor it through our mockery. The Bulwer-Lytton Fiction Contest has been giving awards to the worst opening sentence in an imaginary novel every year since 1982. The winning sentences, while they almost always elicit groans, additionally elicit a pause from me in which I consider how truly entertaining bad writing can be. To wit, consider this entry from 2004 Grand Prize winner, Dave Zobel:

“She resolved to end the love affair with Ramon tonight . . . summarily, like Martha Stewart ripping the sand vein out of a shrimp’s tail . . . though the term “love affair” now struck her as a ridiculous euphemism . . . not unlike “sand vein,” which is after all an intestine, not a vein . . . and that tarry substance inside certainly isn’t sand . . . and that brought her back to Ramon.”

Bad books are also edifying. Every once in a while when I’m plowing my way through a paragraph that is awkward, ugly, or totally unjustifiable, I ask myself how I would fix it. I admit that I occasionally answer myself by saying “I wouldn’t include this godawful subplot in the first place” or even “By never being born,” but more often I identify with the author’s plight. Good writing is hard to do, and so I like to think that by providing fellow writers with a sympathetic reading even in the lowest, slimiest trenches of the written word, I will myself someday be the recipient of such generosity. Or at least, I’ll improve my own technique by trying to pull something redeeming out of the wreckage.

But beyond the personal skill level, bad writing can teaches us about ourselves and our world in a way that is just as valuable as those cracked open by greater scribes. When I was in school for my Masters degree I wrote a paper on fanfic. Those who have stumbled upon this phenomenon know the horror that awaits you at websites such as lotr.net or harrypotterfanfiction.com. They consist of colonies of amateur writers who are very passionate about a particular television show, movie, or series of books. Their passion moves them to write stories using the characters and context of their original inspiration. And some of it is bad. Very, very bad. Here’s a typical summary:

“My story takes place when Arwen is 15. It begins in Rivendell, but somehow Arwen’s path will lead her to a typical American high school where she has fallen in love with the mortal boy who sits next to her in trigonometry.”

When I was researching this paper my reading experience was often similar to depilation, but just as often I was left with a small kernel of empathy and goodwill for these intrepid writers. After all, if only unwittingly, they have allowed us to see into some of the most intimate situations and challenging problems of their lives to date. The author above is clearly using writing to lessen the sting of an unrequited math class crush. It may not sound like Shakespeare, but she’s using writing to reach out and connect with others through her own pain—an instinct I think the bard would approve of.

The Da Vinci Code is doing the same thing, but for our entire society. To capture the imagination of so many, Dan Brown evidently has plucked a few resounding chords on the heartstrings of his massive readership. It’s easy to extrapolate how years of pent-up resentment at the Catholic church, and a growing willingness to reconsider women’s inferior place in most spiritual disciplines are attractive emotional veins to tap.

Finally, because of their popularity, bad books reflect our period in history in the way that no timeless classic can. The stalwarts of the Canon are not as useful as reality television, entertainment tabloids and, yes, popular novels in defining and characterizing our particular cultural moment. Perhaps having your finger on the pulse of the culture, especially pop culture, isn’t important to some, but it is to me. When I’m old I want to be a relic of my epoch. I want to make my grandchildren roll their eyes when I begin making book and movie recommendations five decades or so out of date. I want to know what’s going on now, so that when now is over, I’ll know what happened.

This all reminds me of Emile, a book by Rousseau proposing a method of education to bring about an ideal citizen. The crucial part of his plan was the first couple of decades of the child’s life, when he was to live a relatively isolated existence in the countryside, reading only carefully chosen books to promote the utmost mental and moral development.

Game over. I spent my first decade reading, ravenously, avidly, anything I could get my hands on, from a copy of my dad’s Esquire magazine to The Babysitters’ Club #173. My second decade was less productive because I spent it trying to read books I didn’t and couldn’t possibly understand. I knew that by selecting texts off the shelf labeled Literature in Waldenbooks I could impress teachers and relatives, but although my 13-year-old eyes traveled carefully over every word of Madame Bovary, they did so in vain. I had no way to truly connect with what I was reading. And so now I would gladly leave Emile to his empty countryside and pile of Signet Classics in favor of an utterly unfettered smorgasbord of reading.

The biggest flaw in my Read Everything plan is my eventual death. I’m hoping I have a few good years left, but after those I will have to move on, and I don’t know how many books I’ll be able to take with me (or how much time I’ll have to read them). So should I really be investing this precious remaining time reading any old supermarket claptrap? Shouldn’t I be desperately cramming my brain with only the choicest nuggets that literature has to offer?

I don’t intend to abolish “good” books from my life, or from my commute. Rather, I plan to choose what to read by…(drumroll)…reading what interests me, whether that book is generally considered good, bad, or indifferent. I plan to continue reading said book only as long as it continues to interest me, after which I will toss it aside lightly, or should the situation arise, I will do as Dorothy Parkers suggests and throw it aside with great force.

For a while, anyway. If I turn into a drooling moron, maybe I’ll blow the dust off the cover of my copy of Anna Karenina and get cracking. But otherwise, you’ll find me forging deeper into my brave new world in the Fiction section of Waldenbooks, hunting down a copy of The Devil Wears Prada.Labels: Dananator

Read more!