In Which Christopher Castle Loses a Job and Acquires an Overcoat in the Same Evening

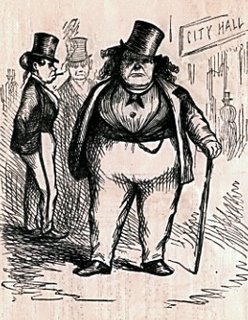

An unattractive man by nature, Mr. Walpole was not improved by anger. In fact, his acquaintances often commented that although he was ordinarily ugly, anger transformed him into a creature of the most repulsive sort. And he was often angry, to the great dismay of his wife who, like most other wives, would have preferred a handsome husband.

When Mr. Walpole was enraged, his chest expanded to twice its size, his face grew mottled, and a vein throbbed dangerously in his forehead. His fingers thickened, his eyes bugged out, his lips turned purple, his toes curled, and his buttocks clenched. On occasions of particular wrath, his knees locked and his throat swelled, rendering him mute and immobile. Like so, he boiled in impotent anger until someone came near enough for him to punch, which always calmed him somewhat.

Next to his temper, fashion was Mr. Walpole’s most extraordinary feature. He cleverly deflected attention from his ill-formed figure with silk shirts and striped suits. His hats were tilted just right, never crushed or crumpled, and his cufflinks gleamed. He wore the finest of overcoats and dinner jackets and business suits. Swathed in rich fabrics, Mr. Walpole was an appalling combination of ugliness and beauty, like a turkey in peacock feathers.

Mr. Walpole was well known around town as an eccentric and a distinguished patron of the symphony. He was loathed by the presidents and directors of this fine institution, and feared by the lower echelon of customer service representatives–the box office agents, ushers, and bartenders. He had been a subscriber for a number of years, which meant that, to the great dismay of these officials and representatives, a specific seat was reserved for him in the audience every week. And it was a very good seat.

It so happened that this seat was on the center aisle in the third row of the right section. This was the best seat in the house for many reasons. It was close to the musicians, but not so close that Mr. Walpole was wetted by the spittle that shook free from the saxophones. The third row on the aisle was also nice because there was more legroom. Mr. Walpole’s legs were long and thick, and it was difficult for him to fold these appendages neatly within the bounds of a normal seat. He liked to stretch his legs out into the aisle, and cross his ankles in a dignified manner.

All of these were perfectly good reasons for Mr. Walpole to prefer the third row, center aisle. Above them all, however, was the fact that his seat was directly in front of the flute section. And in the flute section, directly in front of his seat, was a particular flute player with long, golden hair and soft eyes. And for all of its obvious advantages, Mr. Walpole’s seat had only one disadvantage: it was directly next to the seat of a certain Mrs. Walpole. His wife did not enjoy the symphony, but attended only to watch her husband watching the flute player. This unnerved him a little, which was the reason that Mrs. Walpole preferred her seat.

One night, in the middle of the season, the curtain rose to Mr. Walpole’s intense displeasure, and Mrs. Walpole’s joy. The flute section had been moved to the left side of the orchestra for some odd reason or another that only conductors understand. Mr. Walpole stood up and strode off down the aisle; Mrs. Walpole stretched out her legs and enjoyed the symphony for the first time.

Despite Mr. Walpole’s angry phone calls to the director and the president, the conductor, and the governor, the orchestra remained settled in this new position, and the officials stood their ground. The flute section would not be moved, just for him, they said. So Mr. Walpole changed his tactics. If they would not move the orchestra, he stated, they must move him. And with a sigh of relief, the officials wiped their hands of Mr. Walpole, and deposited him in the laps of the customer service representatives.

“Call the box office,” they said, and laughed to themselves. So Mr. Walpole called the box office and demanded his subscribed seat be moved. He knew the seat he wanted– the third row, center aisle on the left side.

“I’m sorry, Sir.” Said the young woman at the box office. “But that seat is subscribed.” It was, indeed, the seat of Mr. Marlin Archer, a gentle soul who had once played the saxophone in a blues band until he lost a hand to frostbite in a bird-watching expedition. He had attended every symphony performance for the last forty years– the first thirty-five of which he had attended with his wife, who loved Beethoven, until she passed away while hunting grouse in October. Everyone knows grouse hunting in the fall is a risky business. Now, alone, Mr. Archer continued to attend the symphony every week, in the very same seat. This seat had been passed on to him by his father, who had sat in the same spot for fifty years before him; it had originally been passed to Mr Archer’s father by his grandmother, who had sat there since the theater was built many, many years ago.

“That is not acceptable.” Said Mr. Walpole to the box office girl, when she explained the circumstances. “I am a subscriber, and I will have that seat.”

“I’m sorry, Sir, but you cannot have that seat.” Repeated the girl. She explained again, eternally patient as customer service representatives are wont to be. She offered him other seats, all very nice seats on the left side, all available. But to each, he replied,

“Is it the third row, center aisle, left side?”

“No, but it is the fourth row, three seats in from the center aisle.”

“Unacceptable.” There was no legroom there, you see.

“Fifth row, center aisle.”

“Too far away.”

“Second row, center aisle.”

“Too close.” By now, Mr. Walpole was shouting and the patient girl was crying. When she was no longer intelligible through her sobs, she was replaced by a fresh, patient voice.

“How may I help you, Sir?” The same conversation was repeated until the second patient voice was hoarse.

“Let me speak to your superior!” Mr. Walpole shouted at the third box office girl, who handed the telephone to the manager.

“How may I help you, Sir?” Asked the manager as he passed a box of tissues around the office. Mr. Walpole shouted his demands.

“That is simply impossible, Sir.” The manager said politely. After much explaining and repeating, Mr. Walpole threatened to remove his patronage from the symphony. Box office people and other people of little authority are much distressed by this sort of threat, for they imagine their great cultural institution crumbling into dust all because they angered an ill-tempered patron. Box office people are always the first to be blamed for such catastrophes.

The manager did not know what to do. He worried and pondered, and kept Mr. Walpole on hold for a very long time, which just made him angrier. And then, the manager had an idea.

“Hello, Sir? We have pulled some strings here and I’m happy to say you may have that seat.”

“It’s about time.” Mr. Walpole barked, and hung up. The manager ordered the first box office girl to make a phone call. He told her what to say and, at last free of the affair, laughed at his brilliance. Still sniffling, the box office girl sighed and dialed Mr. Archer’s number. When he answered, she forced her voice to sound cheerful.

“Hello, Mr. Archer? Congratulations! I’m calling to inform you that because of your long and magnificent patronage to the symphony, your seat has been upgraded to the second row.”

Christopher Castle was, at this time, employed by the symphony orchestra in the coat-check room. He stood behind a counter every evening and took people’s coats. He hung them up on numbered hangers and gave each patron a slip of paper printed with a matching number. For this task he received a modest salary, plus tips, if he was lucky. He had learned through experience that the placement of the tip jar had a lot to do with how full it would be by the end of the night. In his early days, the tip jar embarrassed him somewhat, and he tried to make it inconspicuous, yet to encourage tips by smiling and handling coats with a delicate touch. He had placed the jar off to the side, partially hidden behind a little framed sign that read “Don’t Forget Your Overcoat.” Since no one could forget their overcoat in December, no one read the sign; therefore, his tip jar went unnoticed.

When his first paycheck barely covered his rent, Christopher decided that pride and honor would have to be less conspicuous than the tip jar. He placed it in the center of the counter and stood behind it so that patrons had to hand their coats over the jar. He made a few tips this time, but noticed that those who dropped coins into the jar did so with a hunted, almost hostile glance up at him.

Intimidation seemed to work moderately well, but Christopher Castle was not entirely comfortable being intimidating He moved the jar a little to the right, and stood a little to the left. When people handed him their coats, they furtively dropped some change in the jar when Christopher swept their cloaks into the back room– except Mr. Clark from the first row, who took change out of the jar to use at poker night.

This was by far the most effective placement for a tip jar. Christopher shared his discovery with the girl who worked at the gift shop, the bartenders, and the cookie-seller, all of whom tried it to their immense satisfaction. Christopher became very popular at the symphony.

All in all, Christopher enjoyed his job. He was allowed to attend concerts for free on his off-nights. He sat high up in the balcony and closed his eyes, learning to appreciate the booming grandeur of Beethoven, the pips and squeaks of Bartok, and the fanciful stories of Stravinksy. Perched above the orchestra in the magnificent domed hall, he felt that even he, in his own small way, was supporting the musicians; helping to create the glorious music they produced, night after night.

Until one night when their music was gloriously interrupted. Mr. Walpole arrived triumphant at the symphony, his wife walking eagerly beside him. She was looking forward to the concert, for he had not told her about the new seat. Mrs. Walpole was much dismayed a short time later to discover that, while her husband had changed his seat, hers was very much in the same place.

Mr. Walpole carried in his arms a large package; so large, in fact, that he had difficulty getting it through the lobby doors, which made him angry. The bartenders sighed, the gift store girl took a deep breath, and the cookie person threw a napkin over the cookies, for Mr. Walpole always touched each one and never bought anything. Christopher Castle took out his finest coat hanger and straightened his tip cup. He never received a tip despite the extra care he took of Mr. Walpole’s coat, but he never stopped hoping for one.

People stood aside for Mr. Walpole as he passed, and looked after him as he carried his colossal box across the lobby. It slipped and tilted in his arms, pulling him off kilter and into ladies and gentlemen that leapt gingerly out of his path. In this awkward manner, Mr. Walpole made his way to the coat-check counter. He placed the box at his feet, and swept his overcoat from his shoulders. It was long and black and fine. The gold buttons shone and the collar stood stiff at attention. His cufflinks were anchors and the hem was clean. It was the coat of a duke. If it had been red, it would have been the coat of a king.

The coat rippled richly as he tossed it over the counter, into Christopher’s waiting arms. While Christopher hung the overcoat in the back room, Mr. Walpole took his box into his arms with much groaning and puffing. His frustration grew. He was angry with the saleswoman who had enclosed the gift in such an awkward box, forgetting that he had asked for the gift to be wrapped as grandly as possible, so as to be more impressive upon its presentation to the flutist later that evening.

As Mr. Walpole struggled with the package, patrons lined up behind him to check their coats. Men coughed meaningfully and ladies tapped their shoes. Mr. Walpole became angrier and angrier as important people grew increasingly frustrated at his struggle. Finally, he heaved a corner of the package onto the counter. Christopher disappeared behind it.

“Sir…” his voice piped from the other side of the package, “I don’t think it will fit.” Mr. Walpole growled dangerously.

“It damn well will.” He barked, and shoved the box with both hands. It creaked and wedged above the counter. From the other side of the package, Christopher suggested,

“Perhaps you might keep this in your car.”

“I certainly will not.” Mr. Walpole leaned against he package and shoved with his shoulder. “This is the coat-check and you are to stow my belongings. Now pull!” He shouted. The patrons in line muttered to themselves. The lady behind him fanned herself with a program and took off her mink coat, draping it over her arm. She tapped Mr. Walpole on the shoulder. Without turning, he shouted something extremely rude to the tapper.

“Well, goodness!” She huffed. Her husband handed her his glass of red wine and rolled up his shirtsleeves.

“Now see here…” The husband growled. Mr. Walpole stepped back with a determined grunt and the line stumbled behind him. With a roar, he threw himself forward and rammed the entire side of his hefty body against the package. With a tremendous crunch, the package jumped across the counter, into Christopher Castle’s chest, and knocked him flat. The counter caught Mr. Walpole in the stomach and sent him sprawling backwards just as the man with rolled shirtsleeves swung his fist. He missed, however, for Mr. Walpole scattered the patrons with flailing limbs, and knocked the wine glass from the lady’s hand. Red wine poured over her white mink coat. Amidst screeches and spills, Mr. Walpole picked himself up and planted both fists on the counter, his face turning a startling shade of purple, the vein above his eye pulsing, his knees locked, his throat swollen, he could only bark, “Argh! Argh!”

And to Christopher Castle, who looked up, startled, from the floor, Mr. Walpole was the Devil’s very likeness. Other angry faces rose up around Mr. Walpole. Weeping, the lady held up her ruined mink. For a full minute, no one spoke. They all watched Mr. Walpole’s mouth working soundlessly and his eyes twitching.

“You!” He shouted finally, pointing at Christopher, who struggled to stand up. “You pushed me.” The angry faces all turned to Christopher.

“You.” The lady moaned, “You ruined my mink.” The miserable scene that followed was not a highlight in Christopher Castle’s young life. The manager was summoned, apologies were skillfully executed, and coats were at last hung on their hangers. In his own heart, the manager could not blame Christopher Castle, for he had his own experience with Mr. Walpole’s foibles. He was wise enough to know, however, that it would be the end of the symphony if he blamed a patron for such a catastrophe, so he publicly berated Christopher and took away his tip jar. The manager promised the patrons that Christopher would never work at the symphony again– after this evening, of course, because they were short-staffed.

Humiliated, Christopher handed Mr. Walpole a numbered ticket. He snatched the slip of paper, grunted loudly, and, still purple, strode away followed by his wife, who never checked her coat, or indeed removed it at all. As the rest of the patrons filed into the theater, the manager winked at Christopher and promised him a good reference. Christopher found himself both disgraced and unemployed. He sat miserably on the stool behind the counter, and waited in agony for the end of the evening.

Christopher’s night was ruined, but the patrons settled calmly into their seats. No one had been injured, after all, the lady had another three minks at home, and Mr. Walpole had his new seat. There were only two unhappy concertgoers that night, and both of their eyes were on Mr. Walpole. Mrs. Walpole sat on the right side of the room, watching her husband smiling up at the flutist from the left. Mr. Archer huddled in his second row seat, gazing sadly back at the seat his family had warmed for generations.

From the coatroom, Christopher could hear the concert begin. He shuddered to think of how close he had come to single-handedly ruining the symphony. Instead, it had ruined him. No longer would he sit high up in the balcony under the great dome, for his musical education had ended here among the overcoats. Inside the hall, the trumpets sounded in mourning, the clarinets wailed, the French horns moaned; they all seemed to grieve for Christopher Castle. He leaned back, hugged by empty sleeves, and closed his eyes.

Many patrons prefer to close their eyes at the symphony– to block out distractions, they say. Mr. Walpole was not one of them. He enjoyed the music as much as the next person, but it was not Beethoven or Mozart who drew him back, week after week. The music had become mere background to his true pleasure– catching the furtive glances of the soft-eyed flutist. While others rested sightlessly beside him, Mr. Walpole hardly dared blink. He particularly enjoyed the pauses between overtures. In these few, silent moments, as the patrons rubbed their eyes and rustled and coughed, the flutist could devote to him the full attention of her magnificent gaze. He leaned forward as the first overture came to a close with a single high, unwavering note.

Mr. Walpole watched as the flutist smiled out into the audience. It was a coy and intimate smile– a smile he knew all too well. But she was not smiling at him. Mr. Walpole followed her flirtation to a young man sitting a few chairs down from him. The young man’s eyes were fastened on the little flutist and, as Mr. Walpole watched, he blew her a kiss. She giggled and began to play, her eyes still caressing the young man, who gazed back at her. Mr. Walpole scowled from one to the other, as his wife glowered from across the room, and Mr. Archer shot him moist glances from the second row.

Only Mrs. Walpole and Mr. Archer noticed that something strange was happening to Mr. Walpole in the center aisle, left section seat. His face turned pink, then red, and then purple. A very deep purple. His eyes grew large and seemed to stand out from his head; the vein crawled in his forehead, his knees locked. Mr. Walpole’s thick fingers gripped the arms of his seat until his knuckles turned white. His mouth began opening and closing furiously. Mrs. Walpole half stood, then sat, then stood. The flutist smiled and lowered her flute. She mouthed something very naughty to the young man down the row. Mr. Walpole’s chest expanded horribly and his mouth opened wide, and did not close.

Mrs. Walpole opened her thin little mouth and produced the loudest noise she had ever made. At that moment, the cymbals clashed and the second overture came to a screeching halt among stray trumpet blasts and cacophonous high notes. The ushers flocked down the aisle, coat tails flapping behind them, and struggled to lift Mr. Walpole from his subscribed seat. Even in his unconscious state, he gripped the arms of his seat and clung to them with the bitter grasp of death. The ushers labored in vain to pry his fingers from the velvet and were forced finally to wrench him, seat and all, from the aisle. Held aloft in his velvet chair, head lolling from side to side, heart fluttering ever more faintly, Mr. Walpole was borne down the aisle and out into the lobby.

Mrs. Walpole scampered beneath her husband, catching the change that spilled from his pockets, clasping the hat that jumped from his head, dabbing her eyes with the handkerchief that had floated from his shirtsleeve. Mr. Walpole was swept past the lobby attendants, past Christopher Castle who sat in the coatroom and watched the whole thing from between silk coats, and through the doors to the waiting ambulance. In the silent, stunned hall, the orchestra took up where they left off, and the patrons settled back and closed their eyes against any further distraction.

The ushers, the bartenders, the gift store girl, and Christopher convened in the corner, chattering excitedly. Nothing this wonderful had happened since the choking incident of 1953, in which Mrs. Carmel had chocked on a beer nut in the lobby and been administered the Heimlich by the visiting Irish step dancer. The thrilled group fell silent when the lobby door opened some time later and Mrs. Walpole appeared, shrunken and wet from the rain. She hesitated a moment by the door and the attendants hurried back to their posts. Her eyes swept over the bar, the gift shop, and the cookie girl, and finally came to rest on the coat-check. Christopher straightened his uniform. Mrs. Walpole shuffled to the counter and produced a slip of paper with a number on it.

“The package, please.” She whispered. Christopher hauled the unwieldy, crumpled box onto the counter and Mrs. Walpole sighed. She heaved it up and clasped it to her chest. Pink tissue paper poked out from one corner. Tilting precariously from side to side, she started for the door. Christopher cleared this throat.

“Ma-am,” he said, “there’s an overcoat.”

“Oh.” Mrs. Walpole turned, “He won’t be needing that anymore.” And she smiled.

And that is how Christopher Castle lost a job and acquired an overcoat in the same evening.

Labels: Trusty Editor Croftie

5 Comments:

i HEART christopher castle- the everyman/woman (which is a very challenging thing to be!). clearly, croft is the voice of our generation. more CC!

you already know what i think of your fiction but i wanted to mention how sophisticated it was to begin your piece with nary a glimpse of CC until a reader is firmly along for the ride.

by the way i heart the 'I heart' phrase very little. a pox upon you Oline and your youthful exubrance! here's to the nouveau olde!

ok toesock. so i've been rocking the "i heart" thing a little hard lately. will try to lay off the huckabees!

Well done, Croft! The setting calls to mind a very similar cultural institution in which a Croft, a Rumphius and a Bombshell crossed paths, gloriously. We will always remember the joy of eating stolen cookies in the coat check, and the rage of an upset patron.

I very much enjoy the narrator's voice in this piece. It seems to belong to a different time, and is therefore in amusing contrast to mentions of phones and cars. Well done, Croft.

I heart it.

*grumble* *grumble* i heart *grumble*

Post a Comment

<< Home