Stars, Tabloids, and Sex Taboggons

Oline on Warhol’s “Jackie” & “Liz”

That great connoisseur of success, sex, celebrity, and culture, Mr. Andy Warhol, once wrote, “The red lobster’s beauty only comes out when it is dropped into the boiling water.” It’s a line that neatly sums up Warhol’s own fixation with the extremes of “Stars, Death, and Disasters,” all three of which are currently explored in a retrospective at the Chicago Museum of Contemporary Art. Among Warhol’s most interesting canvases are portraits of two stars whom death and disaster stalked throughout their bizarrely intertwined tabloid lives: Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and Elizabeth Taylor.

According to Warhol, the best reason to be famous is being able to “read all the big magazines and know everybody in all the stories. Page after page it’s just all people you’ve met.” Among the tabloid players with whom Warhol was personally acquainted was “Jackie” Kennedy, the most profitable cover girl of the 1960s and 70s movie magazines. A special breed of tabloid and the forerunner of today’s US Weekly, the movie magazines were devised by the film studios as a publicity tool. Since readers held little loyalty for individual publications and based their purchases almost exclusively on subject matter, the industry depended upon newsstand sales to an extraordinary extent. Readers were drawn primarily to magazines with naughty headlines and provocative cover photographs; to this end, editors rushed to find public figures that exercised broad appeal and kept readers interested over long periods of time. Much as popcorn kept movie theaters afloat after the advent of television, so “Jackie” stories salvaged the movie magazines: The prevailing editorial policy was to regularly feature the First Lady alongside “any lady or gentleman of the screen and television who misbehaved.”

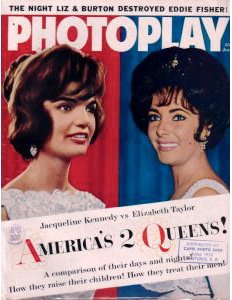

Among the contemporary misbehaving ladies and gentlemen, Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton reigned supreme and, despite the absence of any legitimate connection, the movie magazines desperately tried to link “Jackie” with the Burtons, her “magazine relatives.” During “Jackie’s” Kennedy years, the couples served as foils for one another; the Burtons’ racy exploits emphasized the Kennedys’ elegance while “Jack” and “Jackie’s” élan exaggerated “Burton” and “Liz’s” indulgence. Photoplay even devoted major coverage to an examination of the Kennedys’ “Marriage & Taste” versus the Burtons’ “Passion & Waste.” With the death of “Jack,” the tabloids featured the remaining threesome under headlines insinuating romantic intrigues, clandestine meetings, and unorthodox sexual proclivities. There were ostensibly benevolent intentions; the tabloids sought to unite “Jackie” and the Burtons because “It would truly be a new, fun, fun world for Jackie– for the Burtons are fun, fun people.” Consequently, “Jackie”-“Burton”-“Liz,” which persisted as a tabloid phenomenon well into the late 1970s, pervaded the national consciousness. According to sociologist Irving Schulman:

Women loved to hate “Liz,” an actress who seemed constantly on the brink of personal disaster; they simply loved Mrs. Kennedy. In the words of pop-philosopher Wayne Koestenbaum, “Liz was trash; Jackie was royalty.” “Jackie” and “Liz” themselves held antithetical positions in the American consciousness, as exemplified in the 1962 magazine, JACKIE and LIZ. The one-shot commemorative opened with a page that explained “Why We Are Comparing JACKIE and LIZ.” “They shine in completely different constellations and exert a completely different emotional and moral effect upon us,” the editors wrote. “To compare them [ . . . is] a way for us to examine the natures of the stars we create, and in the process discover something about ourselves.” What we, the reader, should discover was clarified in a simple headline on the same page: “LIZ TAYLOR: A Warning To American Women; JACKIE KENNEDY: An Inspiration to American Youth.” “Jackie” was “WOMAN OF THE YEAR,” “Mistress of the Washington Merry Go-Round,” and “First in the Hearts of Her Countrymen.” She “KEEPS HER MAN HAPPY,” is “SURROUNDED BY LOVE” and only “Leaves Her Home For Service.” In very stark contrast, “Liz” was the “SENSATION OF THE YEAR” and “STAR OF THE ROMAN SCANDALS.” “A Woman Without a Country” who was “Caught in the mad Marriage-Go-Round” and “SURROUNDED BY FEAR,” she faced “A THREATENING TOMORROW.”

To gossip columnist Fanny Hurst, “Jackie’s” place in people’s affections was a barometer of the national well-being. “Jackie’s” “high standards of dignity” and “family life” had won the admiration of the nation’s women, whereas “Liz” had “steered her sex toboggan down a dangerous run.” Despite the onslaught of “unsavory Taylor-Burton headlines, the shabby stories of shabby lies, of multiple marriages, infidelities, divorces, broken homes, displaced children,” Americans still recognized and craved the family values that “Jackie” represented. In their disparagement of Elizabeth Taylor, the movie magazines sent a valuable message to readers whose own marriages might be lacking “the fire of passion” and who might be tempted to follow “Liz’s” less traditionally feminine example by steering their own “sex toboggans” along her perilous path.

Collectively, the tabloid narrative implies a rivalry between “Liz” and “Jackie,” which was most often cast in terms of the women’s sexuality. When “Jackie,” supposedly rankled by “Liz’s” libidinous activities on the Cleopatra set, did not attend the movie’s Washington premier, TV Radio Mirror declared it: THE DAY JACKIE ‘SLAPPED’ LIZ! In the article, prudish “Jackie” frowned upon “Liz’s” amorous exploits and “Liz’s” doings appeared magnified in contrast to “Jackie’s” extreme restraint. “Liz’s” indiscretions were genuinely startling by contemporary standards, but she appears even more depraved when considered alongside “Jackie’s” pristine morality. In later years, with “Jackie’s” slide toward Greek decadance, the rivalry would continue to dominate the headlines: AMERICA’S TWO FALLEN QUEENS; ONE NIGHT WITH JACKIE’S HUSBAND MAKES LIZ’ DREAM COME TRUE; THE NIGHT ONASSIS TURNED TO LIZ; JACKIE DISGRACED AS ARI BOOZES IT UP WITH LIZ IN PUBLIC BAR; TWO DESPERATE WOMEN GAMBLE ALL; LIZ’ PREMARITAL HONEYMOON PLANS INVOLVE JACKIE’S HUSBAND!

“Jackie’s” very appearance in the movie magazines suggested a fundamental shift from their original role as an advertising vehicle for motion picture stars. It is obvious that readers were intrigued with “Jackie” and “Liz” for entirely different reasons. Both were exaggerated icons– “Liz” the voluptuous vixen and “Jackie” the aloof patrician. However, “Liz,” an actress, was in fact selling a product– herself and her movies. Because “Jackie” had nothing to hawk, her life itself was turned into a movie, “a lifie,” for the public’s entertainment. By the early-1960s, “the tabloid newspaper was almost exactly analogous to a movie theater,” and “Jackie’s” life was the feature presentation, played out on newsstands across the country.

In time, the differences in the unique relationships readers developed with both women would become more apparent. “Liz’s” connection to the public derived from total revelation. In Life the Movie, film and culture commentator Neal Gabler succinctly catalogues “Liz’s” shifting societal role:

In contrast, “Jackie’s” audience was tantalized by what she withheld. Her adamant refusal to reveal herself or her private life created a vast expanse of ignorance, which proved fertile ground for wildly speculative assertions and implausible fantasies. Because “Jackie” refused to participate in the tabloid pageant, the magazines reached out to readers—inviting them to select a wedding dress for “Jackie’s” remarriage, to suggest a hairstyle, and to pass judgment upon her hem lengths. In a manner eerily evocative of American Idol, the movie magazines fostered the public’s sense of interactivity in Mrs. Kennedy’s life. After her remarriage in 1968, Motion Picture even invited readers to vote to “BACK JACKIE,” as if their support would have a real effect upon the new Mrs. Onassis. (And this was not just a wacky 60s phenomenon. Following Mrs. Onassis’ death in 1994, the National Enquirer invited readers to send sympathy cards, which the magazine thoughtfully promised to bundle and ship to the Kennedy family.)

In American culture, “Jackie” acted as a tabula rasa, onto which everyone from little girls to frustrated housewives could project their fantasies of glamour and romance. As an Onassis acquaintance once said: “Jackie was nothing; an ordinary American woman with average tastes and some money. She was a creation of the American imagination.” Yet, within the tabloid culture, “Jackie” heralded a new age, in which “an ordinary housewife writ large” could become a star. And as Warhol admited, “More than anything people just want stars.”

That great connoisseur of success, sex, celebrity, and culture, Mr. Andy Warhol, once wrote, “The red lobster’s beauty only comes out when it is dropped into the boiling water.” It’s a line that neatly sums up Warhol’s own fixation with the extremes of “Stars, Death, and Disasters,” all three of which are currently explored in a retrospective at the Chicago Museum of Contemporary Art. Among Warhol’s most interesting canvases are portraits of two stars whom death and disaster stalked throughout their bizarrely intertwined tabloid lives: Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and Elizabeth Taylor.

According to Warhol, the best reason to be famous is being able to “read all the big magazines and know everybody in all the stories. Page after page it’s just all people you’ve met.” Among the tabloid players with whom Warhol was personally acquainted was “Jackie” Kennedy, the most profitable cover girl of the 1960s and 70s movie magazines. A special breed of tabloid and the forerunner of today’s US Weekly, the movie magazines were devised by the film studios as a publicity tool. Since readers held little loyalty for individual publications and based their purchases almost exclusively on subject matter, the industry depended upon newsstand sales to an extraordinary extent. Readers were drawn primarily to magazines with naughty headlines and provocative cover photographs; to this end, editors rushed to find public figures that exercised broad appeal and kept readers interested over long periods of time. Much as popcorn kept movie theaters afloat after the advent of television, so “Jackie” stories salvaged the movie magazines: The prevailing editorial policy was to regularly feature the First Lady alongside “any lady or gentleman of the screen and television who misbehaved.”

Among the contemporary misbehaving ladies and gentlemen, Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton reigned supreme and, despite the absence of any legitimate connection, the movie magazines desperately tried to link “Jackie” with the Burtons, her “magazine relatives.” During “Jackie’s” Kennedy years, the couples served as foils for one another; the Burtons’ racy exploits emphasized the Kennedys’ elegance while “Jack” and “Jackie’s” élan exaggerated “Burton” and “Liz’s” indulgence. Photoplay even devoted major coverage to an examination of the Kennedys’ “Marriage & Taste” versus the Burtons’ “Passion & Waste.” With the death of “Jack,” the tabloids featured the remaining threesome under headlines insinuating romantic intrigues, clandestine meetings, and unorthodox sexual proclivities. There were ostensibly benevolent intentions; the tabloids sought to unite “Jackie” and the Burtons because “It would truly be a new, fun, fun world for Jackie– for the Burtons are fun, fun people.” Consequently, “Jackie”-“Burton”-“Liz,” which persisted as a tabloid phenomenon well into the late 1970s, pervaded the national consciousness. According to sociologist Irving Schulman:

If new photographs worthy of inclusion at deadline were not to be had, art directors arranged jigsaw cutouts for Jackie-Burton-Liz, and in a very short time indeed a national conditioned response was established. Purchasers who saw a photograph of Jacqueline Kennedy would think immediately of Elizabeth Taylor and what she was doing; conversely a photograph of [ . . . ] Elizabeth Taylor would conjure up an image of Mrs. Kennedy.The “Jackie”-“Liz” connection would become so integrated into the popular culture that in the Hollywood treatment of the “Jackie” story, The Greek Tycoon, the lead female character was named “Liz.”

Women loved to hate “Liz,” an actress who seemed constantly on the brink of personal disaster; they simply loved Mrs. Kennedy. In the words of pop-philosopher Wayne Koestenbaum, “Liz was trash; Jackie was royalty.” “Jackie” and “Liz” themselves held antithetical positions in the American consciousness, as exemplified in the 1962 magazine, JACKIE and LIZ. The one-shot commemorative opened with a page that explained “Why We Are Comparing JACKIE and LIZ.” “They shine in completely different constellations and exert a completely different emotional and moral effect upon us,” the editors wrote. “To compare them [ . . . is] a way for us to examine the natures of the stars we create, and in the process discover something about ourselves.” What we, the reader, should discover was clarified in a simple headline on the same page: “LIZ TAYLOR: A Warning To American Women; JACKIE KENNEDY: An Inspiration to American Youth.” “Jackie” was “WOMAN OF THE YEAR,” “Mistress of the Washington Merry Go-Round,” and “First in the Hearts of Her Countrymen.” She “KEEPS HER MAN HAPPY,” is “SURROUNDED BY LOVE” and only “Leaves Her Home For Service.” In very stark contrast, “Liz” was the “SENSATION OF THE YEAR” and “STAR OF THE ROMAN SCANDALS.” “A Woman Without a Country” who was “Caught in the mad Marriage-Go-Round” and “SURROUNDED BY FEAR,” she faced “A THREATENING TOMORROW.”

To gossip columnist Fanny Hurst, “Jackie’s” place in people’s affections was a barometer of the national well-being. “Jackie’s” “high standards of dignity” and “family life” had won the admiration of the nation’s women, whereas “Liz” had “steered her sex toboggan down a dangerous run.” Despite the onslaught of “unsavory Taylor-Burton headlines, the shabby stories of shabby lies, of multiple marriages, infidelities, divorces, broken homes, displaced children,” Americans still recognized and craved the family values that “Jackie” represented. In their disparagement of Elizabeth Taylor, the movie magazines sent a valuable message to readers whose own marriages might be lacking “the fire of passion” and who might be tempted to follow “Liz’s” less traditionally feminine example by steering their own “sex toboggans” along her perilous path.

Collectively, the tabloid narrative implies a rivalry between “Liz” and “Jackie,” which was most often cast in terms of the women’s sexuality. When “Jackie,” supposedly rankled by “Liz’s” libidinous activities on the Cleopatra set, did not attend the movie’s Washington premier, TV Radio Mirror declared it: THE DAY JACKIE ‘SLAPPED’ LIZ! In the article, prudish “Jackie” frowned upon “Liz’s” amorous exploits and “Liz’s” doings appeared magnified in contrast to “Jackie’s” extreme restraint. “Liz’s” indiscretions were genuinely startling by contemporary standards, but she appears even more depraved when considered alongside “Jackie’s” pristine morality. In later years, with “Jackie’s” slide toward Greek decadance, the rivalry would continue to dominate the headlines: AMERICA’S TWO FALLEN QUEENS; ONE NIGHT WITH JACKIE’S HUSBAND MAKES LIZ’ DREAM COME TRUE; THE NIGHT ONASSIS TURNED TO LIZ; JACKIE DISGRACED AS ARI BOOZES IT UP WITH LIZ IN PUBLIC BAR; TWO DESPERATE WOMEN GAMBLE ALL; LIZ’ PREMARITAL HONEYMOON PLANS INVOLVE JACKIE’S HUSBAND!

“Jackie’s” very appearance in the movie magazines suggested a fundamental shift from their original role as an advertising vehicle for motion picture stars. It is obvious that readers were intrigued with “Jackie” and “Liz” for entirely different reasons. Both were exaggerated icons– “Liz” the voluptuous vixen and “Jackie” the aloof patrician. However, “Liz,” an actress, was in fact selling a product– herself and her movies. Because “Jackie” had nothing to hawk, her life itself was turned into a movie, “a lifie,” for the public’s entertainment. By the early-1960s, “the tabloid newspaper was almost exactly analogous to a movie theater,” and “Jackie’s” life was the feature presentation, played out on newsstands across the country.

In time, the differences in the unique relationships readers developed with both women would become more apparent. “Liz’s” connection to the public derived from total revelation. In Life the Movie, film and culture commentator Neal Gabler succinctly catalogues “Liz’s” shifting societal role:

Taylor’s early appeal as a life performer was her willingness to expose her private sexuality, first with [Eddie] Fisher and then with [Richard] Burton, and to provide a voyeuristic charge for those who read about her. Her later appeal, when she was no longer a sex symbol, was her willingness to expose her dysfunctions as melodramatic entertainment: her ballooning weight and subsequent diets, her drug problems, her vexed marriages and romances, her various illnesses.

In contrast, “Jackie’s” audience was tantalized by what she withheld. Her adamant refusal to reveal herself or her private life created a vast expanse of ignorance, which proved fertile ground for wildly speculative assertions and implausible fantasies. Because “Jackie” refused to participate in the tabloid pageant, the magazines reached out to readers—inviting them to select a wedding dress for “Jackie’s” remarriage, to suggest a hairstyle, and to pass judgment upon her hem lengths. In a manner eerily evocative of American Idol, the movie magazines fostered the public’s sense of interactivity in Mrs. Kennedy’s life. After her remarriage in 1968, Motion Picture even invited readers to vote to “BACK JACKIE,” as if their support would have a real effect upon the new Mrs. Onassis. (And this was not just a wacky 60s phenomenon. Following Mrs. Onassis’ death in 1994, the National Enquirer invited readers to send sympathy cards, which the magazine thoughtfully promised to bundle and ship to the Kennedy family.)

In American culture, “Jackie” acted as a tabula rasa, onto which everyone from little girls to frustrated housewives could project their fantasies of glamour and romance. As an Onassis acquaintance once said: “Jackie was nothing; an ordinary American woman with average tastes and some money. She was a creation of the American imagination.” Yet, within the tabloid culture, “Jackie” heralded a new age, in which “an ordinary housewife writ large” could become a star. And as Warhol admited, “More than anything people just want stars.”

Labels: Trusty Editor Oline

2 Comments:

Amazing how, for the better part of two decades, a whole genre of publications could report on a completely fabricated relationship between two women whom they'd christened as doppelgangers. Also amazing that movie magazines would use a former First Lady as a cover fixture. Can you imagine if British pop music magazines were forever reporting on Queen Elizabeth's sexcapades?

thank heavens we were spared queen liz's sexcapades! blech!

Post a Comment

<< Home